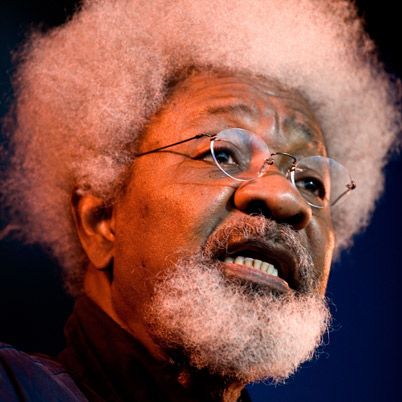

About Wole Soyinka

Wole Soyinka is a world-renowned writer, rights activist, polemicist and Nobel Prize Laureate. With a career spanning more than six decades, Soyinka is widely regarded as one of the most important literary figures of the twentieth century, and his works have had a significant impact on African and world literature.

Biography

Nigerian playwright and political activist Wole Soyinka received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986. He was born in 1934 in Abeokuta, near Ibadan, into a Yoruba family and studied at University College in Ibadan, Nigeria, and the University of Leeds, England. Soyinka, who writes in English, is the author of five memoirs, including Aké: the Years of Childhood (1981) and You Must Set Forth at Dawn: A Memoir (2006), the novels The Interpreters (1965) and Season of Anomy (1973), and 19 plays shaped by a diverse range of influences, including avant-garde traditions, politics, and African myth.

Soyinka’s poetry similarly draws on Yoruba myths, his life as an exile and in prison, and politics. His collections of poetry include Idanre and Other Poems (1967), Poems from Prison (1969, republished as A Shuttle in the Crypt in 1972), Ogun Abibiman (1976), Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems (1988), and Selected Poems (2001).

An outspoken opponent of oppression and tyranny worldwide and a critic of the political situation in Nigeria, Soyinka has lived in exile on several occasions. During the Nigerian civil war in the 1960s, he was held as a prisoner in solitary confinement after being charged with conspiring with the Biafrans. In 1997, while in exile, he was tried for, convicted of, and sentenced to death for antimilitary activities, a sentence that was later lifted.

Soyinka has taught at a number of universities worldwide, among them Ife University, Cambridge University, Yale University, and Emory University.

Biography

by Biography

Who Is Wole Soyinka?

Wole Soyinka was born in Nigeria and educated in England. In 1986, the playwright and political activist became the first African to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. He dedicated his Nobel acceptance speech to Nelson Mandela. Soyinka has published hundreds of works, including drama, novels, essays and poetry, and colleges all over the world seek him out as a visiting professor.

Early Life

Wole Soyinka was born Akinwande Oluwole “Wole” Babatunde Soyinka on July 13, 1934, in Abeokuta, near Ibadan in western Nigeria. His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was a prominent Anglican minister and headmaster. His mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, who was called “Wild Christian,” was a shopkeeper and local activist. As a child, he lived in an Anglican mission compound, learning the Christian teachings of his parents, as well as the Yoruba spiritualism and tribal customs of his grandfather. A precocious and inquisitive child, Wole prompted the adults in his life to warn one another: “He will kill you with his questions.”

After finishing preparatory university studies in 1954 at Government College in Ibadan, Soyinka moved to England and continued his education at the University of Leeds, where he served as the editor of the school’s magazine, The Eagle. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English literature in 1958. (In 1972 the university awarded him an honorary doctorate).

Plays & Political Activism

In the late 1950s Soyinka wrote his first important play, A Dance of the Forests, which satirized the Nigerian political elite. From 1958 to 1959, Soyinka was a dramaturgist at the Royal Court Theatre in London. In 1960, he was awarded a Rockefeller fellowship and returned to Nigeria to study African drama.

“The greatest threat to freedom is the absence of criticism.”

Soyinka is also a political activist, and during the civil war in Nigeria he appealed in an article for a cease-fire. He was arrested for this in 1967, and held as a political prisoner for 22 months until 1969.

Nobel Prize and Later Career

In 1986, upon awarding Soyinka with the Nobel Prize for Literature, the committee said the playwright “in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence.” Soyinka sometimes writes of modern West Africa in a satirical style, but his serious intent and his belief in the evils inherent in the exercise of power are usually present in his work. To date, Soyinka has published hundreds of works.

In addition to drama and poetry, he has written two novels, The Interpreters (1965) and Season of Anomy (1973), as well as autobiographical works including The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972), a gripping account of his prison experience, and Aké ( 1981), a memoir about his childhood. Myth, Literature and the African World (1975) is a collection of Soyinka’s literary essays.

“Against my rational instincts, I believe that we have here a genuine case of a born-again democrat,” he said. Ultimately, “the real heroes of this exercise have been the Nigerian people and that gingers me up.”

Now considered Nigeria’s foremost man of letters, Soyinka is still politically active and spent the 2015 election day in Africa’s biggest democracy working the phones to monitor reports of voting irregularities, technical issues and violence, according to The Guardian. After the election on March 28, 2015, he said that Nigerians must show a Nelson Mandela–like ability to forgive president-elect Muhammadu Buhari’s past as an iron-fisted military ruler, according to Bloomberg.com.

Personal Life

Soyinka has been married three times. He married British writer Barbara Dixon in 1958; Olaide Idowu, a Nigerian librarian, in 1963; and Folake Doherty, his current wife, in 1989. In 2014, Soyinka revealed he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and cured 10 months after treatment.

Biography

Writing became a therapy. I was reconstructing my own existence. It was also an act of defiance.

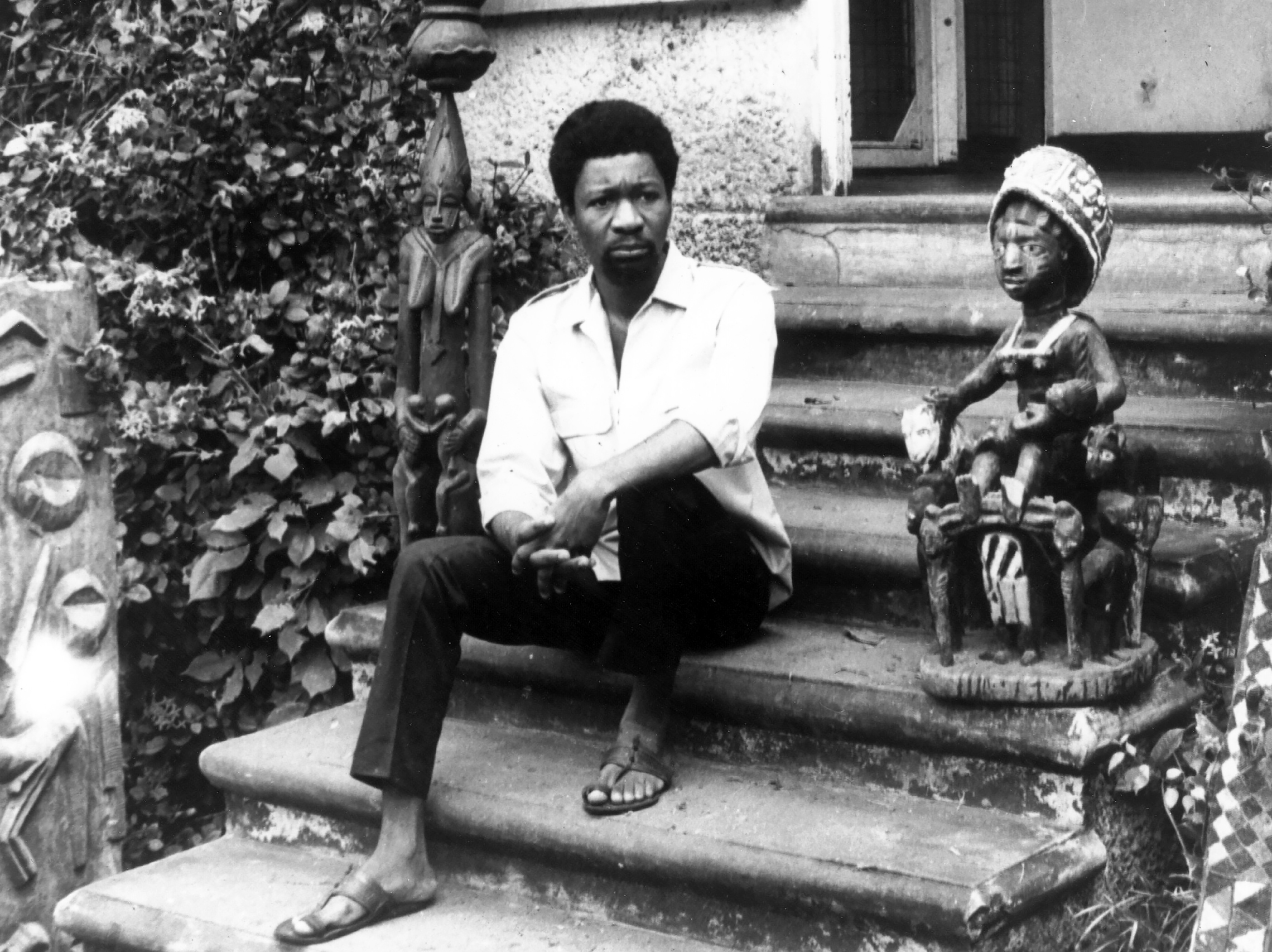

Akonwande Oluwole “Wole” Soyinka was born in Abeokuta in Western Nigeria. At the time, Nigeria was a Dominion of the British Empire. British religious, political and educational institutions co-existed with the traditional civil and religious authorities of the indigenous peoples, including Soyinka’s ethnic group, the Yorùbá people, who predominate in Western Nigeria. As a child, Soyinka lived in an Anglican Christian enclave known as the Parsonage. Soyinka’s mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, was a devout Anglican; in his memoirs, Wole Soyinka calls his mother “Wild Christian.” His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was headmaster of the parsonage primary school, St. Peter’s. Known as “S.A.,” Wole Soyinka calls him “Essay” in his memoirs. Although the Soyinka family had deep ties to the Anglican Church, they enjoyed close relations with Muslim neighbors, and through his extended family — particularly his father’s relations — Wole Soyinka gained an early acquaintance with the indigenous spiritual traditions of the Yorùbá people. Even among practicing Christians, belief in ghosts and spirits was common. The young Wole Soyinka enjoyed participating in Anglican services and singing in the church choir, but he also formed an early identification with Ogun, the Yorùbá deity associated with war, iron, roads and poetry.

Soyinka’s mother, a shopkeeper, joined a protest movement, led by her sister Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, against the traditional ruler, the Alake of Abeokuta, who ruled with the support of the British colonial authorities. When the Alake levied oppressive taxes against the shopkeepers, Mrs. Ransome-Kuti, Mrs. Soyinka, and their followers refused to pay, and the Alake was forced to abdicate.

Thanks to his father, young Wole Soyinka enjoyed access to books, not only the Bible and English literature but to classical Greek tragedies such as the Medea of Euripides, which had a profound effect on his imagination. A precocious reader, he soon sensed a link between the Yorùbá folklore of his neighbors and the Greek mythology underlying so much of western literature.

He moved quickly from St. Peter’s Primary School to the Abeokuta Grammar School and won a scholarship to the colony’s premier secondary school, the Government College in Ibadan. At this boarding school, he continued to distinguish himself in his studies, writing stories and acting in school plays, the beginning of his lifelong preoccupation with the practical aspects of theatrical performance.

After graduation at age 16 from the Government College, Soyinka deferred immediate admission to university life and moved to the colonial capital, Lagos, to work in an uncle’s pharmacy for two years before entering university. During this period of personal independence, he began writing plays for local radio. In 1950, he entered the University at Ibadan. Two years later, won a scholarship to the University of Leeds in England, and left Africa for the first time.

In England, he joined a close-knit community of West African students. The petty racism they encountered in Britain seemed less important than the reports they read from South Africa of black Africans being subjected to legally enforced racial discrimination in their own country by the white-led apartheid government. Along with his fellow African students, Soyinka imagined a pan-African movement to liberate South Africa. He went so far as to enlist in the British program of student military education, in hopes that he could use this training in a future campaign against the apartheid regime in South Africa. He dropped out of the program during the Suez Crisis, when it appeared that students might be called up to serve in Egypt. As Britain prepared to leave Nigeria, students like Soyinka were excused from further military service.

After graduating from the University of Leeds, Wole Soyinka continued to study for a master’s degree while writing plays drawing on his Yorùbá heritage. His first major works, The Swamp Dwellers and The Lion and the Jewel, date from this period. In 1958, The Lion and the Jewel was accepted for production by the Royal Court Theatre in London. Beginning in the late 1950s, the Royal Court was the major venue for serious new drama in Britain. Soyinka interrupted his graduate studies to join the theater’s literary staff. From this post, he was able to watch the rehearsal and development process of new plays at a time when the British theater was entering a period of renewed vitality. His own next major work was The Trials of Brother Jero, expressing his skepticism about the self-styled elite of black Nigerians who were preparing to take power from the British colonial regime.

In 1960, Soyinka received a Rockefeller Foundation grant to research traditional performance practices in Africa. Nigeria was poised to become independent from Britain, and Soyinka’s play A Dance of the Forest, another satire of the colonial elite, was chosen to be performed during the independence festivities. Soyinka joined the English faculty at the University of Ibadan. He also formed a theater company, 1960 Masks, to produce topical plays, employing traditional performance techniques to dramatize the many issues arising from Nigerian independence. His writings, including his 1964 novel, The Interpreters, were bringing him fame outside his own country, but he faced increasing difficulties with censorship inside Nigeria. Independence from Britain had not brought about the open democratic society Soyinka and others had hoped for. In negotiating the independence of the country, Britain had overestimated the population of the northern region, dominated by Hausa-Fulani people of Muslim faith, and given them greater representation in the national parliament, at the expense of the predominantly Christian peoples of the southern regions: the Yorùbá in the West and the Igbo in the East.

In Western Nigeria, the results of a 1964 regional election were set aside so that a candidate favored by the central government could claim victory. With some friends, Soyinka forced his way into the local radio station and substituted a tape of his own for the recorded message prepared by the fraudulent victor of the election. This escapade caused his arrest and detention for two months, but international publicity led to his acquittal. Following his release, Soyinka was appointed to the English Department of Lagos University, and completed the comedy Kongi’s Harvest, which would be produced throughout the English-speaking world. Soyinka had become one of the best-known writers in Africa, but political developments would soon thrust him into a more difficult role. The discovery of oil in the Southeast in 1965 further heightened ethnic and regional tensions in Nigeria. A 1966 military coup led by Igbo officers was followed by a counter-coup, which installed the young army officer Yakubu Gowon as head of state. Massacres of Igbo living in the North sent more than a million refugees fleeing south, and many Igbo began to call for secession from Nigeria. Hoping to avoid further bloodshed, Soyinka traveled in secret to meet with the secessionist General Ojukwu and urged a peaceful resolution. When Ojukwu and the Eastern forces declared an independent Republic of Biafra, Soyinka contacted General Obasanjo of the Western forces to urge a negotiated settlement of the conflict, but Obasanjo sided with the national government, and a full-scale civil war ensued. Soyinka’s friend, the poet Christopher Okigbo, joined the Biafran forces and was killed in action.

Soyinka was accused of collaborating with the Biafrans and went into hiding. Captured by Nigerian federal troops, he was imprisoned for the rest of the war. From his prison cell, he wrote a letter asserting his innocence and protesting his unlawful detention. When the letter appeared in the foreign press, he was placed in solitary confinement for 22 months. Despite being denied access to pen and paper, Soyinka managed to improvise writing materials and continued to smuggle his writings to the outside world. A volume of verse, Idanre and Other Poems, composed before the war, was published to international acclaim during his imprisonment. By the end of 1969, the war was virtually over. Gowon and the Nigerian federal army had defeated the Biafran insurgency, an amnesty was declared, and Soyinka was released. Unable to return immediately to his old life, he repaired to a friend’s farm in the South of France. While recuperating, he wrote an adaptation of the classical Greek tragedy The Bacchae by Euripides. Across the millennia, the story of a state destroyed by a sudden eruption of senseless violence had acquired a special resonance for Soyinka. Another volume of verse, Poems from Prison, also known as A Shuttle in the Crypt, was published in London.

Soyinka returned to Nigeria to head the Department of Theater Arts at the University of Ibadan. The 1970s were a productive decade for Wole Soyinka. He oversaw stage and film productions of his play Kongi’s Harvest and wrote one of his most compelling satirical plays, Madmen and Specialists. His prison memoir, The Man Died, was published in 1972, followed by a novel, The Season of Anomy. He traveled to France and the United States for productions of his plays. When political tensions resurfaced, unresolved by the civil war, Soyinka resigned his university post and went to live in Europe, lecturing at Cambridge and other universities. Oxford University Press published his Collected Plays in 1974. One of his greatest works appeared the following year, the poetic tragedy Death and the King’s Horseman. After a number of years in Europe, Soyinka settled for a time in Accra, Ghana, where he edited the literary journal Transition. His column in the magazine became a forum for his continued commentary on African politics, in particular for his denunciation of dictatorships such as that of Idi Amin in Uganda.

In 1975, General Gowon was deposed, and Soyinka felt confident enough to return to Nigeria, where he became Professor of Comparative Literature and head of the Department of Dramatic Arts at the University of Ife. He published a new poetry collection, Ogun Abibiman, and a collection of essays, Myth, Literature and the African World, a comparative study of the roles of mythology and spirituality in the literary cultures of Africa and Europe. His continuing interest in international drama was reflected in a new work, inspired by John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera and Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera. Soyinka called his musical allegory of crime and political corruption Opera Wonyosi. He created a new theatrical troupe, the Guerilla Unit, to perform improvised plays on topical themes.

At the turn of the decade, Wole Soyinka’s creativity was expanding in all directions. In 1981, he published the first of several volumes of autobiography, Aké: The Years of Childhood. In the early 1980s, he wrote two of his best-known plays, Requiem for a Futurologist and A Play of Giants, satirizing the new dictators of Africa. In 1984, he also directed the film Blues for a Prodigal. For years, Soyinka had written songs. In the 1980s, Nigerian music, including that of Soyinka’s cousin, the flamboyant bandleader Fela Ransome-Kuti, was capturing the attention of listeners around the world. In 1984, Soyinka released an album of his own music entitled I Love My Country, with an assembly of musicians he called The Unlimited Liability Company.

Soyinka also played a prominent role in Nigerian civil society. As a faculty member at the University of Ife, he led a campaign for road safety, organizing a civilian traffic authority to reduce the shocking rate of traffic fatalities on the public highways. His program became a model of traffic safety for other states in Nigeria, but events soon brought him into conflict with the national authorities. The elected government of President Shehu Shagari, which Soyinka and others regarded as corrupt and incompetent, was overthrown by the military, and General Muhammadu Buhari became Head of State. In an ominous sign, Soyinka’s prison memoir, A Man Died, was banned from publication.

Despite troubles at home, Soyinka’s reputation in the outside world had never been greater. In 1986, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the first African author to be so honored. The Swedish Academy cited the “sparkling vitality” and “moral stature” of his work and praised him as one “who in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence.” When Soyinka received his award from the King of Sweden in the ceremony in Stockholm, he took the opportunity to focus the world’s attention on the continuing injustice of white rule in South Africa. Rather than dwelling on his own work, or the difficulties of his own country, he dedicated his prize to the imprisoned South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela. His next book of verse was called Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems. He followed this with two more plays, From Zia with Love and The Beatification of Area Boy, along with a second collection of essays, Art, Dialogue and Outrage. He continued his autobiography with Isara: A Voyage Around Essay, centering on his memories of his father S.A. “Essay” Soyinka, and Ibadan, The Penkelemes Years.

Meanwhile, Soyinka continued his criticism of the military dictatorship in Nigeria. In 1994, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) named Wole Soyinka a Goodwill Ambassador for the promotion of African culture, human rights and freedom of expression. Less than a month later, a new military dictator, General Sani Abacha, suspended nearly all civil liberties. Soyinka escaped through Benin and fled to the United States. Soyinka judged Abacha to be the worst of the dictators who had imposed themselves on Nigeria since independence. He was particularly outraged at Abacha’s execution of the author Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was hanged in 1995 after a trial condemned by the outside world. In 1996, Soyinka published The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Memoir of the Nigerian Crisis. Predictably, the work was banned in Nigeria, and in 1997, the Abacha government formally charged Wole Soyinka with treason. General Abacha died the following year, and the treason charges were dropped by his successors.Since 1994, Wole Soyinka has resided primarily in the United States. He has taught at a number of American universities, including Emory University in Atlanta, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and Loyola Marymount in Los Angeles. Since moving to the United States, he has written another play, King Baabu, a volume of verse, Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known, and his latest book of memoirs, You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006).

Although Wole Soyinka has always been reticent about discussing his family life, in this volume he makes a particularly touching dedication to his “stoically resigned” children, and to his wife Adefolake, for enduring many years of hardship and dislocation.

Although Wole Soyinka has always been reticent about discussing his family life, in this volume he makes a particularly touching dedication to his “stoically resigned” children, and to his wife Adefolake, for enduring many years of hardship and dislocation.

Although presidential elections were held in Nigeria in 2007, Soyinka denounced them as illegitimate due to ballot fraud and widespread violence on election day. Wole Soyinka continues to write and remains an uncompromising critic of corruption and oppression wherever he finds them.

Quotes

Human life has meaning only to that degree and as long as it is lived in the service of humanity.

I don’t know any other way to live but to wake up every day armed with my convictions, not yielding them to the threat of danger and to the power and force of people who might despise me.

Looking at faces of people, one gets the feeling there's a lot of work to be done.

A tiger doesn't proclaim his tigritude, he pounces.

Achievements & Awards

| Year | Achievement/Award | Awarded by |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Honorary D.Litt. | University of Leeds |

| 1974 | Overseas Fellow | Churchill College, Cambridge |

| 1983 | Honorary Fellow | Royal Society of Literature |

| 1983 | Anisfield-Wolf Book Award | Cleveland Foundation |

| 1986 | Nobel Prize for Literature | Nobel Foundation in Stockholm, Sweden |

| 1986 | Agip Prize for Literature | |

| 1986 | Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic (CFR) | Federal Republic of Nigeria |

| 1990 | Benson Medal | Royal Society of Literature |

| 1993 | Honorary doctorate | Harvard University |

| 1994 | UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for the Promotion of African culture, human rights, freedom of expression, media and communication. | UNESCO |

| 2002 | Honorary fellowship | SOAS |

| 2005 | Honorary doctorate degree | Princeton University |

| 2005 | Akinlatun of Egbaland | The Oba Alake of the Egba clan of Yorubaland |

| 2009 | Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement | American Academy of Achievement |

| 2013 | Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, Lifetime Achievement | Cleveland Foundation |

| 2014 | International Humanist Award | IHEU World Humanist Congress |

| 2017 | Distinguished Visiting Professor in the Faculty of Humanities | University of Johannesburg, South Africa |

| 2017 | "Special Prize" of the Europe Theatre Prize (Premio Europa per il Teatro) | European Commission |

| 2018 | University of Ibadan renamed its arts theater to Wole Soyinka Theatre | University of Ibadan |

| 2018 | Honorary Doctorate Degree of Letters | Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (FUNAAB) |

| 2022 | Honorary Degree | Cambridge University |

| 2015 | Nominated for Special NAFCA Literary Arts Award | NAFCA |

| 2015 | Candidate for the position of Oxford professor of poetry | Oxford University |

Literary Work

Plays

- Keffi’s Birthday Treat (1954)

- The Invention (1957)

- Childe Internationale (1957)

- The Swamp Dwellers (1958)

- A Quality of Violence (1959)

- The Lion and the Jewel (1959)

- The Trials of Brother Jero (1960)

- A Dance of the Forests (1960)

- My Father’s Burden (1960)

- The Strong Breed (1964)

- Before the Blackout (1964)

- Kongi’s Harvest (1964)

- The Road (1965)

- Madmen and Specialists (1970)

- The Bacchae of Euripides (1973)

- Camwood on the Leaves (1973)

- Jero’s Metamorphosis (1973)

- Death and the King’s Horseman (1975)

- Opera Wonyosi (1977)

- Requiem for a Futurologist (1983)

- A Play of Giants (1984)

- From Zia, with Love (1992)

- The Detainee (radio play)

- A Scourge of Hyacinths (radio play)

- The Beatification of Area Boy (1996)

- Document of Identity (radio play, 1999)

- King Baabu (2001)

- Etiki Revu Wetin (1983)

- Alapata Apata (2011)

- “Thus Spake Orunmila” (in Sixty-Six Books (2011)

Essays

- “Towards a True Theater” (1962)

- Culture in Transition (1963)

- Neo-Tarzanism: The Poetics of Pseudo-Transition

- Art, Dialogue, and Outrage: Essays on Literature and Culture (1988)

- From Drama and the African World View (1976)

- Myth, Literature, and the African World (1976)

- The Blackman and the Veil (1990)

- The Credo of Being and Nothingness (1991)

- The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis (1996)

- The Burden of Memory – The Muse of Forgiveness (1999)

- A Climate of Fear (the BBC Reith Lectures 2004, audio and transcripts)

- New Imperialism (2009)

- Of Africa (2012)

- Harmattan Haze On An African Spring (2012)

- Of Power and Freedom – Vol 1 (2022)

- Of Power and Freedom – Vol 2 (2022)

- Beyond Aesthetics: Use, Abuse, and Dissonance in African Art Traditions (2019)

Novels

Short stories

- A Tale of Two (1958)

- Egbe’s Sworn Enemy (1960)

- Madame Etienne’s Establishment (1960)

Films

- Kongi’s Harvest

- Culture in Transition

- Blues for a Prodigal

Poem Collections

- Telephone Conversation (1963) (appeared in Modern Poetry in Africa)

- Idanre and other poems (1967)

- A Big Airplane Crashed into The Earth (original title Poems from Prison) (1969)

- A Shuttle in the Crypt (1971)

- Ogun Abibiman (1976)

- Mandela’s Earth and other poems (1988)

- Early Poems (1997)

- Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known (2002)

Memoirs

Translations

- The Forest of a Thousand Demons: A Hunter’s Saga (1968; a translation of D. O. Fagunwa’s Ògbójú Ọdẹ nínú Igbó Irúnmalẹ̀)

- In the Forest of Olodumare (2010; a translation of D. O. Fagunwa’s Igbo Olodumare)